How to Systematically Troubleshoot HVAC Commissioning Problems

Commissioning HVAC systems for a biopharma facility is a humbling experience. You realize commissioning is far from simply pressing a few buttons and expecting everything to fall into place. Instead, it resembles a highly unpredictable obstacle race where all kinds of challenging problems block your way: underperforming equipment, air balancing issues, room pressure fluctuations, high humidity, automation software malfunction, and excessive vibrations, to name a few.

But commissioning is also the time when no one wants to see the project’s progress slowing down. After the usual delays in design and construction, project teams try hard to rush and squeeze in commissioning. On the contrary, however, HVAC commissioning often turns messy and drags, defying all expectations. Why?

If commissioning is all about solving problems, one would expect experienced teams to follow a systematic approach to troubleshooting. However, very often, the approach is haphazard, somewhat like treating a patient without a proper diagnosis and administering random medicines. Ignoring the basics of the problem-solving process comes at a steep price: confusion, chaos, frustration, blame game, time delays, and cost escalations.

How can a commissioning team avoid adding more pain to the painful problems they have to anyway face?

Treatment without diagnosis

Imagine visiting a doctor who prescribes medicines and even surgery without first examining the symptoms and carefully diagnosing the disease. Could be deadly, isn’t it? But this is exactly what happens during commissioning, especially when facing tricky problems like room pressure or humidity fluctuations.

Over the years, I have seen many cases where commissioning problems survived longer than necessary when we tried to kill them without a proper diagnosis. However, one such case is particularly memorable from a project in southern China.

Since the outside conditions varied a lot (Summer: 38.7 °C /90% RH, Winter: 0.2 °C / 30% RH), all Air Handling Units (AHUs) were equipped with steam heating coils and humidifiers. But despite the correct equipment design, during commissioning a tricky issue surfaced: low room temperature and high humidity. As soon as this problem was identified, someone in a position of power pointed the finger at the control valves in the steam lines that regulated the steam supply to the AHUs. From that point on, the focus shifted to solving the “real” problem: How to fix the steam control valves?

After heated arguments with the valve supplier, months of delay, and thousands of dollars, the steam control valves were replaced with new ones for all AHUs. But sadly, the problem persisted.

Exhausted and under even greater pressure, people desperately searched for other causes and finally found the steam traps installed in the return steam lines were flooding with the condensate water. Once the flooding was fixed, the original problem—room temperature and humidity—was resolved right away. But by then, commissioning had been delayed by months with thousands of dollars going down the drain.

This episode of jumping to a solution and getting hurt may seem insane, but it is hardly a unique case. If we could hold off the urge to jump to the solutions, what would an ideal troubleshooting process look like?

Troubleshooting: Three simple steps

Taking a cue from good doctors, the troubleshooting could be reduced to just three steps:

- Examine: Start by looking at and framing the problem

- Analyze: Diagnose the ailment

- Solve: Treat the patient

The process looks deceptively simple; very often teams jump to step three while ignoring the first two, complicating both the problem and their own lives.

#1: Examine: Start by looking at and framing the problem

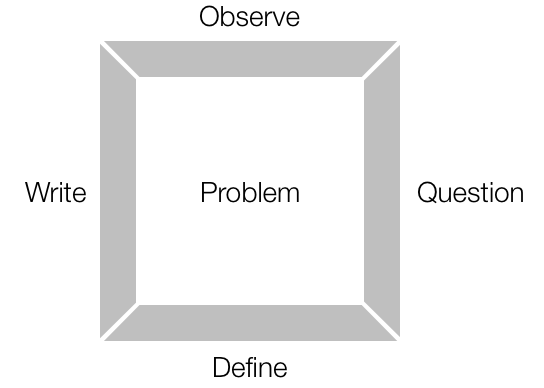

Like a photo frame, framing a problem has four sides to it:

- Observe

- Question

- Define

- Write

Observe

Although it may look exaggerated, the ability to observe (see, listen, touch, smell) an unacceptable situation itself is a big leap toward resolving it. Personally, whenever I get involved in a problem, my first action is not to solve it, but to visit the site and observe the situation with my own eyes. But observation alone is not enough.

Question

After observing, if we really want to grasp a complicated issue, the best way is to ask the right questions: What, when, where, who, and assumptions.

- What

- Expected: What’s expected/standard/normal in the current situation? Add facts/numbers.

- Actual: What’s actually happening or has happened? Add facts/numbers.

- When

- When did it happen? Timeline or sequence of events?

- Where

- Where exactly is the problem? Which part, system, or location?

- Who

- Who is involved in the problem? Who is affected by the problem?

- Assumptions

- Any things that we don’t really know but are assuming at this stage?

If you really ask these questions when facing a tricky problem, you’ll be surprised at how many gaps and variations there are in people’s understanding of the same issue.

Define

Having observed and asked pertinent questions, define the problem, which is basically the gap between the expected and actual. If you’re expecting the maximum humidity to be 60%, but the actual is 63-65%, the gap between the two is the “problem.” All problems should be discussed in the context of (a) expected, (b) actual, and (c) gap.

Write

The final step is to write down the problem statement, which should be clear, concise, and precise. Why write? Well, writing forces issues to be more specific and concrete–and separate from causes and solutions.

To our minds, especially if we have some experience, all of this may seem like unnecessary or theoretical work, but it could well be the real difference between dancing around a problem in circles or expeditiously resolving it.

If the commissioning team in China had defined the problem properly, considerable time and cost could have been saved.

A problem well stated is half solved.

Charles Kettering

#2: Analyzing problems (diagnosis after examination)

If we don’t deliberately step back and spend some time framing a “problem,” our instinct is to jump to solutions. It may work if a problem is straightforward. But very often “jumping to solutions” approach doesn’t work, leading to multiple people throwing different solutions at different variations of a problem. This is quite like throwing darts in search of the target.

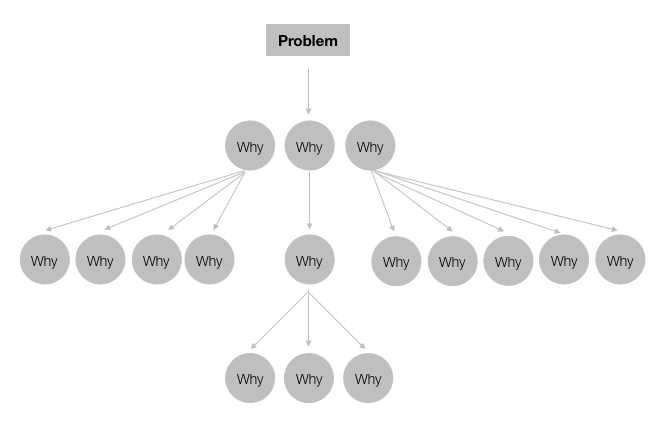

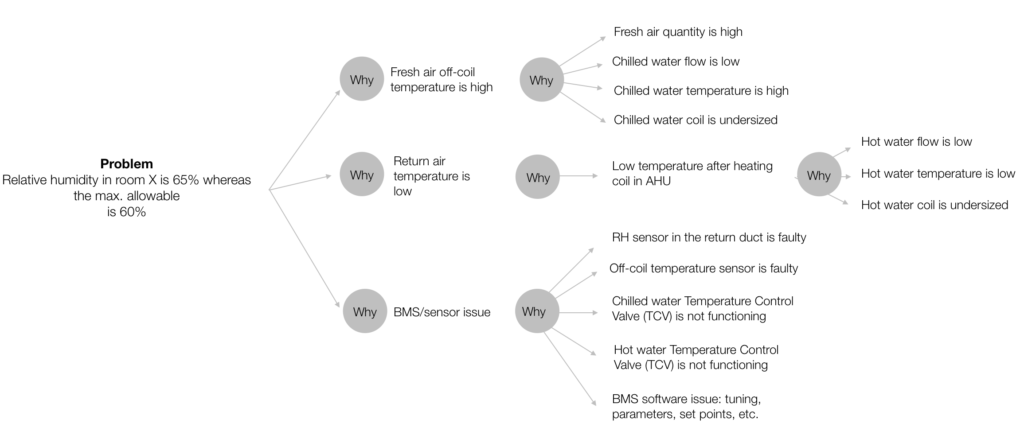

But instead of throwing darts, one could dissect a complicated issue by simply applying the Five Whys, a well-known structured problem-solving technique.

Five Whys technique

At the heart of Five Whys is the premise that “every effect has a cause and, in turn, a cause is an effect for another cause.” To apply this widely used problem-solving technique, first state the problem clearly and then ask “why” three to five times.

Things don’t happen; they are caused to happen.

John F. Kennedy

Here is a simple example of the power of the Five Whys and how it can lead to proper diagnosis from different angles.

You can see how Five Whys helps to suspend our judgment and instead expand our thinking to first consider all possible causes.

#3: Solve: Treat the patient

If any team really goes through the above steps (Examine and Analyze), chances are the solution will start emerging.

If we can really understand the problem, the answer will come out of it, because the answer is not separate from the problem.

Juddu Krishnamurti

But analysis is one thing and really solving an issue conclusively is quite another. At this stage, the key lies in following a well-laid-out strategy to check the potential causes that emerged from the analysis–and fix what’s wrong. The most probable and simple-to-fix causes should be given priority. And also, one must emphasize the importance of evidence to support any conclusions. The rules of the game should be:

- Attack one cause at a time.

- Don’t follow your own hunches, theories, and strategies; follow the analysis and plan agreed with the team.

- Don’t talk, show the evidence.

What if the problem still doesn’t get solved?

Well, HVAC problems are of two types: reversible and irreversible. Reversible problems can be fixed with sensible tweaks, but irreversible problems usually demand huge U-turns that are not feasible at all. For example, at the commissioning stage, you can’t redesign a system or replace major equipment. For irreversible problems, the best course is putting the facts on the table and optimizing for the best. And, of course, learning the bitter lesson.

What if a really tricky issue gets resolved after a painstaking effort? It calls for celebration, which keeps the team energized and motivated.

In conclusion, there is no silver bullet to resolve the HVAC commissioning issues. While knowledge and experience do matter, the very “process” of solving problems matters even more. However, the biggest contribution one can make is not solving problems, but preventing them at the design and construction stages based on past pitfalls. That’s real “experience.”

Finally, leaving you with a point to ponder…

We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.

Albert Einstein